Exploring the intricacies of architectural programs involves delving deeply into the functionality of a building. While certain architects may perceive the functional aspect of a structure as a potential constraint on their creative ingenuity and the pursuit of aesthetic excellence, it is crucial to recognize that neglecting these functional prerequisites could result in everyday users deeming the design a failure.

Hence, architectural programming assumes a pivotal role in every design venture and its associated processes. The question arises: why is this the case?

Understanding the Concept of an Architecture Programme versus a Brief

1. Defining an Architecture Programme:

- Context and Usage: In the realm of architecture, the term “programme” has a specific meaning, distinct from its common usage in relation to schedules or project phases;

- Global Variations: While the term might be used differently across various regions, its core essence remains consistent in the architectural context;

- Unique Characteristics: An architecture programme typically refers to the comprehensive planning and organization of spaces and functions within a building project. It’s a detailed outline of the project’s objectives, requirements, and the envisioned end results.

2. The Role of an Architecture Brief:

- Client-Centric Approach: An architecture brief is essentially a client’s vision put into words. It’s a document that encapsulates the client’s needs, aspirations, and constraints for a project;

- Design Foundation: This brief becomes the cornerstone for architects and designers, guiding them in creating a design that aligns with the client’s expectations;

- Content and Scope: The brief encompasses all aspects of the project, from the functional requirements to aesthetic preferences, and often includes budgetary and time considerations.

3. Differentiating Between Programme and Brief:

- Regional Terminology: While terms like ‘brief’ and ‘programme’ may vary in use globally, with ‘brief’ being more common in Australia and ‘programme’ in the United States, their meanings are distinct;

- Scope and Focus: The programme is generally seen as a component of the brief. It deals more with the spatial and functional aspects of the design, whereas the brief is a broader document encompassing all client requirements;

- Integration in Design Process: Both the programme and the brief play pivotal roles in the architectural design process, but they serve different purposes. The brief sets the stage, outlining the ‘what’ and ‘why,’ while the programme delves into the ‘how’ of space organization and functional planning.

Crafting an Effective Project Brief: Going Beyond the Basics

A well-crafted project brief is more than just a laundry list of programmatic and functional requirements; it serves as the cornerstone of a successful architectural endeavor. While it certainly encompasses the architectural program, it extends far beyond that, offering valuable insights and directives that guide the entire project lifecycle. In this comprehensive guide, we delve into the key components of a robust project brief, shedding light on what it entails and how it can empower architects and designers to excel.

1. Architectural Programme: Defining the Heart of the Project

The architectural program is the heartbeat of any construction project. It encompasses a detailed breakdown of the spaces within the project, aligning them with client needs, user activities, and operational requirements. Here’s what you need to know:

- Client-Centric Spaces: Understanding the unique needs and preferences of the client is paramount. The architectural program should reflect their vision and goals, ensuring their expectations are met;

- User-Centric Approach: Successful designs prioritize the end-users. A thorough understanding of their activities, preferences, and requirements should be at the core of the program;

- Operational Efficiency: The program should consider the functional aspects of the building, optimizing the layout for efficiency and ease of use.

2. Beyond Basics: Scope of Services and Expectations

Going above and beyond, an exemplary project brief clarifies the scope of services expected from the architect or designer. It sets the stage for a transparent and collaborative partnership. Here’s what you should include:

- Comprehensive Service Details: Clearly outline what services the architect or designer is expected to provide. This could range from concept design to project management, ensuring there are no misunderstandings down the line;

- Fee Structure: Discuss the compensation structure. Will it be a fixed fee, hourly rate, or based on a percentage of the project cost? Clarity in financial matters is essential;

- Timelines and Milestones: Define project timelines and milestones. This ensures everyone is on the same page regarding project progress and deadlines.

3. Project Scope of Works: The Soul of the Project

A compelling project brief doesn’t stop at describing the building’s interior; it breathes life into the entire project. It encompasses the site, location, materials, typology, users, and project objectives. Dive deeper into these aspects:

- Site and Location Analysis: Provide insights into the site’s surroundings, topography, and any unique challenges or opportunities it presents. Discuss zoning regulations and local context;

- Materials and Sustainability: Specify the materials to be used and outline any sustainability goals. Are you aiming for LEED certification, energy efficiency, or specific eco-friendly practices?;

- Typology and Aesthetics: Describe the building’s typology (e.g., residential, commercial, industrial) and the desired aesthetic. Share visual references or architectural styles that inspire the project;

- User-Centered Objectives: Outline the primary goals and aspirations of the project. What impact should it have on the users and the community? Define success criteria.

4. Fostering Creativity and Innovation: Room to Explore

A great project brief is not about stifling creativity; it’s about providing a solid foundation for innovation. Encourage designers to explore options while meeting project and program requirements:

- Flexibility: Allow room for creative interpretation within the defined parameters. Designers should feel empowered to propose innovative solutions;

- Research and Experimentation: Encourage research and experimentation to push the boundaries of design. Embrace new materials, technologies, and concepts;

- Collaboration: Foster open communication and collaboration between the client, architect, and design team. Fresh perspectives often lead to groundbreaking designs.

Creating a Comprehensive Program: Understanding the Foundation

Before embarking on the journey of designing a building, it is imperative to create a program that outlines the purpose, functionality, and requirements of the structure. This program serves as the blueprint for architects and designers, ensuring that the end result aligns perfectly with the envisioned goals. Whether you’re planning a cozy residence or a sprawling university campus, the process of defining a program remains essential.

Defining Functional Requirements: The Cornerstone of Your Project

User-Centric Approach: At the heart of any successful building program lies a deep understanding of the users and their diverse needs. Consider the following aspects:

- User Groups and Activities: Identify the various user groups that will occupy the building. Understand their unique activities, preferences, and desires. Whether it’s a family home or a bustling laboratory, comprehending how people will interact with the space is key;

- Space Allocation: Determine the precise spatial requirements for each user group. This includes the physical space they’ll inhabit, ensuring it’s tailored to their activities and comfort;

- Equipment Needs: Delve into the equipment required by users. This involves not only the equipment necessary for their primary activities but also any additional items that must be accommodated, stored, or utilized within the building;

- Equipment Essentials: A thorough inventory of the equipment is crucial for efficient planning.

Consider these points:

- Comprehensive Inventory: Create an exhaustive list of all the physical objects users need to fulfill their tasks. From furniture and machinery to stationery and appliances, every item must be accounted for;

- Storage Solutions: Develop dedicated spaces within the building to house and organize these items effectively. Smart storage solutions can optimize available space while ensuring easy access;

- Specific to Building Type: Recognize that different building types will have unique equipment requirements. For example, a university building may necessitate advanced laboratory equipment, while a home will require furniture and appliances tailored to daily living;

- Vehicle Considerations: In cases where users rely on vehicles for transport, accommodating their needs is vital:

- Vehicle Types: Identify the types of vehicles users will utilize, whether it’s cars, motorbikes, trucks, or even boats. Each requires a specific space allocation and access considerations;

- Storage and Maintenance: Allocate areas for vehicle storage, maintenance, and maneuvering within the building’s design. Proper planning ensures convenience and safety;

- Accessibility: Ensure easy access to and from the building for vehicles, including driveways, parking spaces, and loading docks.

Comprehensive Guide to Operational Requirements in Building Management

Operational requirements form the backbone of effective building management. These are the critical components that ensure the seamless functioning of any building, be it a simple residential house or a complex commercial structure. Operational requirements encompass a wide range of activities, systems, and equipment, each playing a vital role in maintaining the building’s integrity and functionality.

Key Elements of Operational Requirements

- Mechanical Systems: This includes elevators and escalators, which are central to vertical transportation within the building;

- Security Systems: Essential for ensuring the safety and security of the occupants. This covers surveillance cameras, alarm systems, and access control mechanisms;

- Audio-Visual and Communication Systems: Crucial for internal and external communication, as well as for entertainment purposes in certain building types;

- HVAC (Heating, Ventilation, and Air Conditioning): These systems regulate the internal climate of the building, ensuring comfort for all occupants;

- Waste Management: This involves the efficient removal of rubbish, recycling processes, and the disposal of waste.

- Gardening and Landscaping: Particularly relevant for buildings with outdoor spaces, contributing to the aesthetic and environmental value;

- Cleaning and Maintenance: Regular cleaning, including specialized tasks like window washing in high-rises, is vital for maintaining hygiene and appearance.

Enhancing Operational Efficiency

- Consultation with Maintenance Teams: Engaging with those who will operate and maintain the building is crucial. Their insights can provide valuable information on the practical aspects of managing these systems;

- Customization Based on Building Type: The complexity of operational requirements varies significantly based on the building’s purpose and size. A residential house will have vastly different needs compared to a large commercial complex;

- Access Considerations: Ensuring easy access to key areas and equipment for maintenance personnel is vital. This could involve dedicated service corridors or strategically placed maintenance rooms;

- Up-to-Date Technology: Incorporating modern technology can significantly enhance the efficiency and effectiveness of these systems. For example, smart building technologies can automate many operational aspects, leading to better energy management and cost savings;

- Regular Training and Updates: Providing regular training for staff on the latest operational protocols and safety measures can help in maintaining these systems effectively.

Enhancing Design through Strategic Programming

In the realm of architecture and design, the concept of a program serves as a fundamental pillar, guiding the entire design process. Once established, it influences decision-making at various stages, ensuring that the design aligns with the intended purpose and functionality.

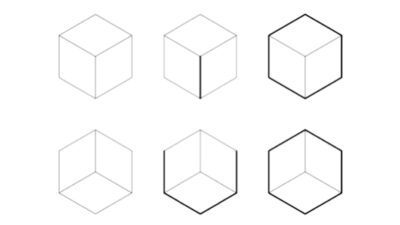

Exploring the Program at Different Scales

To fully harness the potential of a program in design, it’s crucial to consider it at multiple scales. This approach enables the development of comprehensive ideas, innovative concepts, and meticulous design resolution.

[Mega Scale] Building Typology: Defining the Project’s Identity

- Essence of Building Typology: At this scale, the focus is on determining the nature and category of the structure to be designed. This could range from residential buildings like houses, to educational structures like schools, healthcare facilities like hospitals, commercial spaces like shops, or professional environments like office buildings.

In-depth Research for Design Excellence:

- Studying Precedents: Investigating existing examples of similar structures to gain insights into design successes and challenges;

- Aesthetic Exploration: Understanding the visual language and style pertinent to the building type;

- Adopting Best Practices: Learning from industry standards and innovations to enhance functionality and sustainability.

Useful Recommendations:

- Explore a diverse range of examples to broaden design perspectives;

- Engage with stakeholders to understand functional needs and aesthetic preferences;

- Prioritize sustainability and user experience in design choices.

[Macro Scale] Zoning Strategies: Orchestrating Space and Function

Zoning Concept in Design: This involves the strategic grouping of spaces, activities, and uses within a project to create a cohesive and functional layout.

Types of Zones:

- Public vs. Private Zones: Balancing areas accessible to all with private, restricted spaces;

- Entry and Exit Points: Designing welcoming entrances and efficient exits;

- Front of House vs. Back of House: Distinguishing customer-facing areas from operational spaces;

- Circulation Zones: Ensuring smooth movement through corridors, staircases, and elevators;

- Transition Spaces: Creating zones that facilitate a shift from one environment to another, like lobbies or atriums;

- Internal vs. External Areas: Harmonizing indoor spaces with outdoor environments.

Insights and Tips:

- Prioritize user flow and accessibility in zoning decisions;

- Design zones to reflect the building’s identity and purpose;

- Incorporate flexibility in zoning to accommodate future changes.

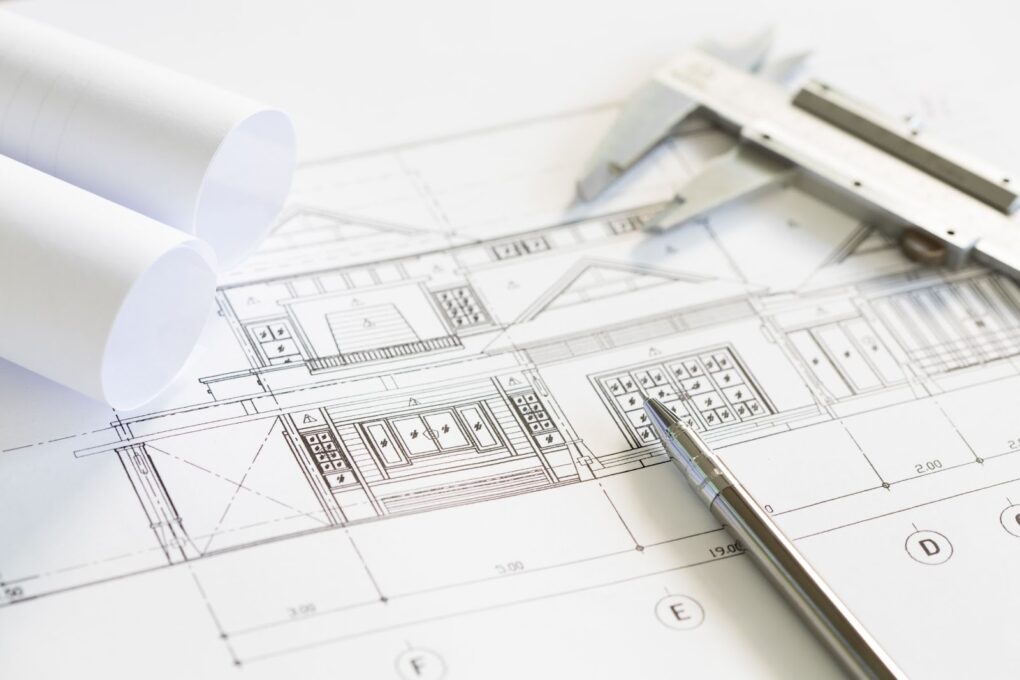

Mastering Spatial Dynamics in Architectural Design

Strategic Planning of Functional Relationships at the Macro Scale

In architectural design, understanding and planning the functional relationships between different spaces is pivotal. This macro-scale consideration focuses on the interplay and connectivity between various areas within a project. Also, explore the captivating world of architectural drawing, where lines and creativity converge to shape the future of design.

Configuring Spatial Relationships:

- Decisions on Space Grouping: Determining whether to cluster similar spaces, like bathrooms, or to distribute them throughout the building for accessibility;

- Strategic Placement of Key Areas: Identifying essential spaces that need direct access from central areas like lobbies, reception, or waiting areas;

- Proximity and Privacy Balance: Deciding which areas should be adjacent for functionality and which should be separated for privacy or noise control;

- Transition and Movement: Crafting the journey between spaces to enhance the user experience, considering both the physical path and the sensory transition.

Recommendations and Insights:

- Conduct thorough user flow analysis to optimize the layout for natural movement patterns;

- Integrate technology for smart navigation and efficient use of space;

- Consider environmental factors like light, sound, and temperature in spatial planning.

Tailoring Individual Spaces at the Micro Scale

Delving into the micro scale, the focus shifts to tailoring individual spaces based on their unique requirements. This involves a detailed consideration of function, operation, aesthetics, volume, and form.

Diverse Space Requirements:

- Understanding Specific Needs: Each space, whether it’s a bathroom, gallery, or performance area, has distinct functional and aesthetic needs;

- Customization for Purpose: Adapting the design to accommodate specific activities, furniture, and equipment;

- Aesthetic and Functional Harmony: Balancing the visual appeal with practicality, ensuring that the space is both attractive and functional.

Design Development Strategies:

- Engage in detailed space planning to ensure optimal use of every area;

- Incorporate flexibility in design to allow spaces to adapt to changing needs or functions;

- Utilize innovative materials and technologies to enhance both functionality and aesthetics.

Practical Tips:

- Maximize natural light and ventilation in spaces to create a healthier environment;

- Incorporate sustainable design practices to reduce environmental impact;

- Consider the human scale and ergonomics in the design to enhance comfort and accessibility.

Conclusion

Many architects with a strong focus on design tend to overlook the importance of programmatic considerations. They perceive it as a potential hindrance to the creative process and the ultimate outcome. Nevertheless, while innovative architectural designs may receive accolades for their aesthetics, they can often prove impractical for users who find themselves unable to furnish a circular space or lack direct access to resources cleverly concealed by the designer within a distant closet, all in pursuit of a minimalist aesthetic. Others may grapple with insufficient daylight or the inconvenience of guiding guests through the kitchen just to reach the dining room.

Embrace the architectural program as an opportunity for exploration and creative expression.