Brazilian architecture reflects a rich blend of cultural influences and environmental adaptations. This article delves into the architectural style prevalent in the region and examines key buildings that chronicle its historical evolution. While exploring the rich world of architectural diversity, from Brazilian architecture with its unique style, features, and iconic structures, let’s now journey to the captivating realm of Hawaiian architecture, where a distinct tropical aesthetic awaits discovery.

Brazil’s architectural journey is deeply rooted in a diverse cultural tapestry, shaped by the need to adapt to the local climate. Over four centuries ago, the city of Santos was established in what is now known as Brazil. During this era, agriculture served as the backbone of society, giving rise to cultural treasures borne from extensive farming practices. It’s worth noting, however, that this period also witnessed the exploitation of the country’s resources.

Within their homes, early settlers often incorporated a priest and a chapel, emphasizing the centrality of family in Portuguese civilization. Meanwhile, Indigenous people and Africans, armed with bows and arrows, continuously strived for a society free from external intrusions by the Crown or the Church. Gilberto Freyre highlighted that the Portuguese were pioneers in placing family at the core of their civilization, in contrast to prioritizing trade. Portugal maintained its tradition of mingling with various ethnicities, distinguishing it from the United States.

Count Keyserling underscored one of Brazil’s remarkable attributes—its ability to foster unity among people despite racial differences. Unlike the United States, where racial conflicts persisted, harmony prevailed in housing estates like Pedregulho, where both Blacks and Norwegians coexisted. However, Brazil grappled with a different issue that threatened internal peace and its future—a rampant and reckless land speculation that acted as a cancerous impediment to development.

Unless this issue is significantly addressed, Brazil’s capacity to produce distinguished architecture will remain compromised, perpetuating political instability. It is widely acknowledged that a nation’s architecture and infrastructure serve as barometers of its development. Consequently, this exploration aims to shed light on Brazilian architecture, tracing its historical roots and contemporary advancements.

Brazil’s Historical and Environmental Influences on Architecture

Brazil’s history is rooted in its settlement in 1520, marking the beginning of a colonial era under Portuguese rule that lasted until the arrival of King Joao VI in 1807, succeeded by his son, Emperor Pedro I of Brazil. During this colonial period, three significant influences shaped Brazilian architecture and daily life: the dominant power of the Church, the discovery of gold in Minas Gerais in the late 17th century, and the importation of enslaved Africans, who played pivotal roles in constructing buildings and cultivating vast plantations producing oranges, sugar, cocoa, coffee, and manioc flour—a staple of the Brazilian hinterlands.

Subsequently, the ongoing impact of the country’s diverse terrain and ever-changing climate emerged as a significant influence. Much of Brazil experiences hot and humid weather, with true cold only found in the southern high mountains. São Paulo, situated on a high plateau, also maintains an annual temperature below 60 degrees.

In contrast, cities like Rio and Salvador endure considerably higher temperatures, while equatorial locations such as Recife and Belém maintain an average temperature of around 80 degrees. The nation’s geographical conditions play a crucial role in understanding its architectural style, making it imperative to grasp these climatic nuances.

It is essential to recognize that the cooler and drier highlands and coastal plains emerged as the most attractive settlement options. Consequently, cities along the coastline, including Santos, Rio, Vitoria, Salvador, Recife, Fortaleza, and Belém, became prime locations for settlement. Roy Nash, in his book “The Conquest of Brazil,” explains that Brazil’s population growth can be attributed not only to heat and humidity but also to the challenges presented by the evergreen hardwood forests that proved daunting for early agriculturists.

Adding to these influences, wood emerged as the primary building material due to its accessibility. However, it never gained widespread popularity in Brazilian construction due to susceptibility to dampness and termite damage, which compromised the structural integrity of wooden buildings.

Brazilian Architecture: A Journey Through Four Centuries

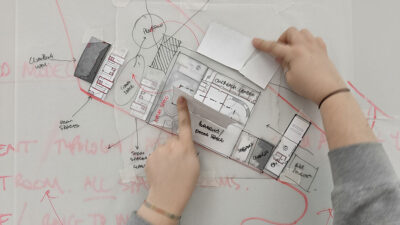

Exploring the architectural heritage of Brazil reveals a captivating narrative of social and historical transformations that unfolded over a mere four centuries. From the initial conquest of the land to the emergence of rural patriarchy, the establishment of a slaveholding society, and the disruptive influences of the industrial revolution and urban planning, each building serves as a testament to the constant evolution of Brazilian society.

The Portuguese Baroque style and Portugal’s 18th-century penchant for azulejos, or intricately designed tiles, played pivotal roles in shaping Brazilian architecture. When the Portuguese first arrived in the 1500s, they encountered primitive Indian huts, but they brought with them a vibrant culture brimming with energy. Within just four years of their arrival, Rio de Janeiro saw the construction of its first stone and mortar houses. In less than a century, many villages transformed into bustling towns characterized by Portuguese-style houses, complemented by churches, monasteries, fortresses, and government edifices dotting the coastal landscape.

However, Brazilian churches, while influenced by the Portuguese Baroque, adopted a distinct character characterized by a more austere framework, adorned with exquisite carvings. This divergence was particularly pronounced in regions like Bahia and Minas Gerais. Let’s delve into some common architectural structures in Brazil:

- Ancient Structures: The São Bento Monastery in Rio stands as a splendid example of early Brazilian architecture, reflecting Benedictine foundations. Cities such as Salvador, Recife, Olinda, and Ouro Preto boasted magnificent monasteries adorned with gold accents and adorned with blue and white Portuguese tiles;

- Village Churches: Typical village churches found on the expansive plateau feature stucco or masonry construction, embellished with orange stone cornices and pilasters. Elaborate gray soapstone frontispieces frame wooden doors adorned with vibrant green or violet accents. The interiors of these churches showcase intricate carvings of leaves, figures, and emblems. Richly ornamented wooden and stucco ceilings take center stage, while stone vaults and domes are notably absent. Elaborate pulpits flank the main body of the church, with tier upon tier of candlesticks, vases, and flowers adorning the altar in the Capela Mor (chancel). Invariably, the sacristy, located at the back or side of the church, outshines even the capela mor with its painted and gilded ceilings, finely crafted jacaranda wood furniture, intricately patterned stone floors, and exquisitely designed central sink;

- Warehouses: As vast fazendas expanded across thousands of acres, enveloping once-virgin forests with coffee trees or sugarcane, the need for colossal warehouses arose in cities like Santos, Salvador, and Belem. These warehouses served as repositories for coffee, sugar, or rubber, awaiting shipment to foreign shores. Along the shores of Recife, rows of warehouses adorned in pale pink, yellow, and blue stand as a testament to Brazil’s trade and commerce. In the city of Salvador, buildings boast broad, flaggable peaks framing seven to nine windows, ascending in symmetrical fashion.

The great wealth generated by these plantations and maritime trade benefited a relatively small elite, many of whom held noble titles like Marquez, Viscount, or Barao, either bestowed upon them in Portugal or acquired during the early years of the Brazilian empire.

In addition to their rural estates, these affluent individuals often constructed ornate stucco or tile-covered solar houses, known as villas, within urban centers. Streets in cities like Rio and others were named after these prominent figures. During certain periods, Portuguese pottery vases and statues with brilliant glazes added a touch of artistry to the global landscape.

The complex relationship between Brazil and its colonial ruler, Portugal, underwent significant changes starting in 1808. Prince Regent Dome Joan VI sought refuge in Rio de Janeiro in the face of Napoleon’s encroachments, marking Rio’s ascension as Brazil’s new capital since 1763. This transformative period witnessed the importation of French artists, spearheaded by Lebreton in 1816, the same year he established a new school.

Lebreton played a pivotal role in disseminating the artistic ideals of Pervier and Fontaine, influencing painters like Debret and architects like Grandjean de Montigny. The latter designed notable structures in Rio, including the Belas Artes school and the Customs House. Auguste-Henri-Victor Grandjean de Montigny assumed the role of the first professor of architecture in the newly formed Imperial Academy, setting the stage for future architectural developments.

Architects like Louis Vauthier contributed to Brazil’s architectural landscape, crafting impressive buildings like the Teatro Santa Izabel in Recife, reminiscent of Paris’s Palais Royal, featuring a dignified porch crowned by grand arched windows in the foyer.

In 1822, with Brazil liberated from Portuguese rule, the nation witnessed significant advancements in official and academic architecture. The mid-19th century introduced a spectrum of architectural styles, from the modest Tuscan to the imposing Gothic, the elegant Moorish, and the charming chalet.

Throughout the 19th century, French Mission architects and their disciples made substantial and sophisticated contributions, guided by principles of common sense, balance, and adaptability to Brazil’s ever-evolving conditions. Le Corbusier’s ideas infused Brazilian architecture with vitality and direction, shaping modern architectural development.

Brazil’s architectural journey continued with the Modern Art Week, first hosted in Sao Paulo in 1922. This event ushered in a new era, emphasizing the spirit of the times through painting and sculpture. It kindled an authentic renaissance that would soon become entrenched in the core values of Brazilian life, drawing from its history, land, and people. Architecture, in turn, felt the impact of the Modern Art Week, with the 1927 competition for the government palace of Sao Paulo state scandalizing observers with its modern design, marking a significant milestone in Brazil’s ongoing architectural evolution.

Characteristics of Brazilian Architectural Design

In contemporary Brazilian architecture, two distinctive features take center stage: expansive glass surfaces adorned with brise-soleil and the innovative use of pilotis, creating open ground floors whenever possible. Let’s delve deeper into these foreign terms and their application in Brazilian design.

Brazilian architects have skillfully incorporated Le Corbusier’s concept of brise-soleil, known as “sunbreaker” in Portuguese, into various architectural expressions. Modern technology, including sunlight graphs and tables, has empowered architects to tackle sunlight-related challenges effectively. Brise-soleil, whether fixed or mobile, can be meticulously designed based on a building’s orientation and purpose, employing a wide array of materials such as reinforced concrete, aluminum, asbestos cement, sheet metal, glass wool sandwiched between glass sheets, plywood sections, or shutters integrated into window frames.

While brise-soleil draws inspiration from traditional methods of sun and glare protection, it constitutes a novel addition to contemporary architecture. Its uniqueness lies in its independence from conventional millwork and its seamless integration with building facades. Even when stationary, brise-soleil elements introduce dynamic qualities through the constant interplay of shadows across surfaces, effectively adding a fourth dimension to architectural compositions, as per Le Corbusier’s vision.

Within the details of brise-soleil and millwork, one may encounter echoes of colonial screens and shutters, blending historical influences with the evolving architectural language, offering innovative solutions to tropical and subtropical climate challenges. Hollow tiles or precast concrete openwork panels, whether simple or intricate, are employed to reduce glare and cast captivating shadow patterns. The use of muxarabis or balustrades further accentuates architectural character.

Moreover, tiles play a pivotal role in emphasizing the non-supporting nature of vertical surfaces, offering a vivid note of regionalism. Patterns derived from a specific number, typically four, or large, representational or abstract tile compositions based on a particular numerical arrangement, contribute to the aesthetic diversity.

However, it’s worth noting that the overuse of azulejos panels in new constructions can sometimes lead to trivial or vulgar outcomes, underscoring the importance of balanced design choices.

The utilization of the pilotis technique at ground level is another hallmark of Brazilian architecture. This approach is particularly well-suited to Brazil’s climate, involving excavating the ground to seamlessly integrate interior and exterior spaces. In Rio de Janeiro, recent legislation exempts ground floors constructed with pilotis from the floor count specified by the Building Code. Although this legislation has limited impact on older neighborhoods, it encourages open and flexible urban planning in newer districts. Pilotis should be closely associated with contemporary city planning and unrestricted land use principles.

Examining existing examples, one can envision the enhanced comfort and appeal of neighborhoods like Copacabana if apartment buildings had been elevated on pilotis. This design choice would have allowed sea breezes to freely circulate through the entire district, extending even to the mountains beyond.

These two defining features—brise-soleil and pilotis—are pivotal in the realm of Brazilian architecture, embodying the spirit of innovation and adaptation to the country’s unique climate and urban context. Now, let’s proceed to explore further aspects of this distinctive architectural landscape.

Iconic Architectural Wonders of Brazil

Gloria Church, Rio de Janeiro

- Construction Date: 1852;

- Architects: Julio Frederico Koelier and Philippe Garcon Riviere.

The Gloria Church stands as an exquisite example of Neo-Baroque architecture. Its interior is adorned with elegant decorations, and the structure itself is crafted from stone, featuring white walls and unique white and blue painted tiles that rise about one meter from the ground. The church boasts finely carved wood decorations on the main altar and side altars, some in the Rococo style and others in the Neoclassical style.

Church of São Miguel das Missões

- Construction Date: Circa 1760;

- Architect: João Batista Primali.

The Church of São Miguel das Missões distinguishes itself among Jesuit mission churches in Brazil with its distinct pedimented portico, set apart from the main body of the building. Unlike most Jesuit architecture, it features low, robust proportions, a squat lateral tower, and a simplified version of the prevailing Baroque style. The facade bears a striking resemblance to the old cathedral of Buenos Aires. Historical challenges, including the Jesuits’ expulsion from Brazil in 1767, may have hindered the church’s completion. It is currently under the jurisdiction of Serviço da Patrimônia Histórica e Artística Nacional and holds the designation of a World Heritage Site.

Brazilian Congress Building

- Construction Date: 1964;

- Architect: Oscar Niemeyer.

The Brazilian Congress building stands as a national monument and an iconic symbol of Brazil, gracing postcards with its avant-garde architecture. Designed by the legendary Oscar Niemeyer, this structure is an artistic representation resembling a set of scales. Two towers flank two domes, housing parliamentary offices. The inverted dome covers the Chamber of Deputies, while the downward-turned dome sits atop the Senate building. A free tour of this Brazilian landmark provides insights into the nation’s history and government.

Co-Cathedral of St. Peter of Clerics, Recife

- Construction Date: 1729;

- Architects: Manuel Ferreira Jacome and Nazzoni.

This church bears the belated influence of Louis XIII style, featuring narrow facade towers above the lower building on a square-sized plot. Nestled around the courtyard of Saint Peter, it stands as one of Recife’s most visited landmarks. The interior is adorned with beautiful muted paintings, and the doors are intricately decorated with rosewood and marble. Notably, the comfortable seating is adorned with fine embroidery and cushions for worshippers.

Fiscal Island

- Construction Date: 1899;

- Architect: Unknown.

Fiscal Island, constructed in 1889, once served as a governmental building for the port authority during the reign of Emperor Dom Pedro II. Its vibrant colors and neo-Gothic style, set against the picturesque backdrop of Guanabara Bay, make it a captivating landmark in Brazil. This monument serves as a poignant reminder of the country’s monarchy under Portuguese rule.

Conclusion

At this point, you’ve gained insight into some fundamental aspects of Brazilian architecture. Our aim in sharing this information is to acquaint you with innovative solutions for managing heat, light, and ventilation on expansive exterior glass surfaces, providing a deeper understanding of architectural approaches to address these challenges.