The quest to define architecture often leads to a plethora of abstract definitions, likening it to a language, a political statement, a collaborative process, an art, a science, or a cultural reflection. Such varied interpretations can be overwhelming, yet at its core, architecture is fundamentally about planning, designing, and constructing buildings and structures.

Architecture: More Than Just Buildings

While a building is simply a structure with walls, a roof, and a floor, true architecture transcends these basic elements. Every architect has their unique perspective on what architecture signifies to them. As both students and practitioners in the field, developing a personal understanding and philosophy of architecture is essential, considering its impact both as a designer and as an inhabitant of architectural spaces.

Architecture is not merely about creating a physical space, but it’s about shaping environments that reflect and respond to the human experience. It’s an art form that blends aesthetics with functionality, where every line, curve, and angle serves a purpose. An architect must consider how spaces will be used, how they interact with their surroundings, and how they make people feel.

In the broader sense, architecture is a reflection of society. It encapsulates cultural values, technological advancements, and environmental concerns. It’s a testament to human ingenuity and creativity. Buildings tell stories of the times they were built in, serving as physical manifestations of historical, social, and economic conditions.

For architects, understanding the context in which they work is crucial. It’s not just about adhering to stylistic trends or the latest technological advancements. It’s about understanding the needs and values of the people who will use those spaces. An architect’s work must resonate with the community it serves, providing not just shelter, but also a sense of belonging and identity.

Furthermore, sustainable architecture has become increasingly important. Architects are now challenged to design with environmental stewardship in mind, creating buildings that are energy efficient, use sustainable materials, and minimize their ecological footprint. This approach demonstrates a commitment to preserving our planet for future generations.

The study of architecture, therefore, is not just about learning technical skills and design principles. It’s a comprehensive education in understanding human behavior, societal needs, environmental stewardship, and artistic expression. It’s about envisioning and creating spaces that enhance the quality of life, inspire, and endure. As architects shape the world’s physical landscapes, they also contribute to the cultural and societal fabric. This profound responsibility makes architecture a truly noble and rewarding profession.

The Human Element in Architecture

Architecture is not a natural phenomenon; it is born from human creativity and innovation. Without human intervention – the excitement, passion, and action to bring ideas to life – architecture would remain an unmaterialized concept. It is a creation for humans, by humans.

Architecture’s Purpose for People

Architects design for the people who will use and experience their creations. The core of every design decision should focus on the internal experience it will provide its inhabitants. This experience can vary widely, depending on the architect’s intent, whether it be an art form, a political statement, or a social gesture, each evoking different internal responses in people.

The internal experience of a space is defined not just by its physical attributes, but also by the emotions and thoughts it evokes. A well-designed space can influence mood, behavior, and even the health of its occupants. It’s about creating an atmosphere, a feeling that resonates with those who interact with the space. Architects must therefore be empathetic, understanding the needs and desires of those who will inhabit their designs.

Design decisions are guided by various factors, including cultural norms, the intended function of the space, and the social context in which it exists. For instance, a public building like a library or museum has a different purpose and audience compared to a private residence. Thus, the architect must consider different approaches to make each space meaningful and functional for its specific use.

Furthermore, architecture can be a tool for social change. Through thoughtful design, architects have the power to address societal issues, promote inclusivity, and foster community engagement. This can be seen in designs that prioritize accessibility, encourage social interaction, or integrate public spaces that serve diverse groups of people. An architect’s work also reflects their personal vision and philosophy. Some may focus on minimalist designs that evoke tranquility and simplicity, while others might create bold, avant-garde structures that challenge conventional aesthetics. Each architect’s style contributes to the rich tapestry of our built environment.

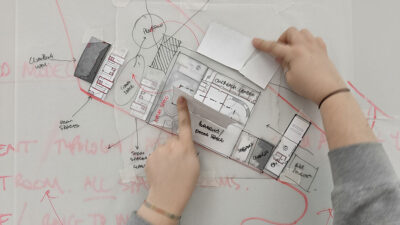

In contemporary architecture, there’s a growing focus on user-centric design. This involves engaging with future occupants during the design process to better understand their needs and preferences. This collaborative approach ensures that the final product is not only aesthetically pleasing but also truly functional and responsive to the people who use it. In essence, architecture is a dialogue between the creator and the user. It’s a multidimensional art form that encompasses the physical, emotional, and social aspects of human experience. The challenge for architects is to balance these elements, creating spaces that are not only beautiful and innovative but also deeply connected to the human experience. This holistic approach is what elevates architecture from a mere building to an expression of human culture and identity.

The Experiential Nature of Architecture

People perceive architecture through sensations, thoughts, and emotions, shaped by their interactions with their environment. The physical senses of sight, sound, taste, smell, and touch all play a role in how architecture is experienced. Additionally, people’s thoughts and emotions in response to architectural spaces can vary greatly, influenced by individual and collective memories and associations.

The Language of Architecture

Architecture communicates through a universal language comprising various elements and principles. This language varies across cultures, times, and places but fundamentally revolves around creating distinct experiences. The conscious use of architectural elements and principles allows architects to shape the sensations, thoughts, and emotions of the inhabitants.

The elements of architecture – like space, form, line, light, color, and texture – are the building blocks of this visual language. Each element plays a critical role in defining the character and functionality of a space. For instance, the use of light can dramatically alter the perception of space, influencing mood and visibility. Similarly, the texture of materials can convey a sense of warmth, austerity, or luxury.

Architectural principles, such as balance, rhythm, proportion, and harmony, guide the organization and arrangement of these elements. They ensure that a building is not just structurally sound but also aesthetically pleasing and comfortable for its users. For example, proportion is crucial in creating spaces that feel well-scaled to human use, while balance contributes to a sense of stability and equilibrium. Moreover, architecture’s universal language extends beyond physical elements to include symbolic and cultural references. Buildings can embody historical styles, reflect local traditions, or incorporate symbolic motifs, connecting people to their heritage and context.

In different cultures and eras, this language has varied interpretations. What is considered harmonious or appropriate in one culture may differ in another. This diversity enriches the global architectural landscape, allowing for a broad range of expressions and styles. The power of architecture lies in its ability to evoke a spectrum of experiences and emotions. A serene chapel, a bustling market, or a solemn memorial, each conveys different feelings and meanings. Architects, therefore, are not just designers of buildings; they are creators of experiences and shapers of environments.

The evolving nature of this language also reflects changes in societal values and technological advancements. As societies evolve, so do architectural norms and practices, adapting to new materials, construction techniques, and environmental concerns. Architecture’s universal language is dynamic and multifaceted. It encompasses a wide range of elements and principles, allowing architects to create varied and meaningful experiences. Through their designs, architects communicate ideas, evoke emotions, and reflect the cultural and temporal contexts of their work, making architecture a truly universal form of expression.

Designing for Experience

Architects have the power to evoke specific responses through the qualities of the spaces they create. Bright, open spaces can convey safety and connection, while small, enclosed areas might evoke feelings of isolation. Understanding the universal responses to certain architectural qualities is key to responsible design.

The Impact of Good and Bad Architecture

Architects must decide the type of experience they wish to create. While some designs might intentionally provoke controversy or discomfort, others aim to foster calm and safety. Good architecture is often seen as that which positively enhances people’s lives, while bad architecture might neglect these experiential aspects. The decision of what experience to create is deeply rooted in an architect’s intent and the purpose of the building. For instance, a museum or a memorial may be designed to evoke contemplation and remembrance, whereas a residential building focuses on comfort and functionality. The choice of experience affects every aspect of design, from the layout to the materials used.

Good architecture often balances aesthetics with functionality. It not only looks appealing but also serves the needs of its users effectively. This includes considerations like accessibility, safety, and comfort. Buildings that neglect these aspects can negatively impact the well-being of their inhabitants, leading to what is often referred to as ‘bad architecture.’ Moreover, architecture has the power to influence social interactions and community dynamics. Thoughtful design can encourage community engagement and interaction, while poorly designed spaces can lead to isolation and disconnection. The role of public spaces in fostering social cohesion is a critical consideration in urban planning and design.

Sustainability is another key factor in determining the quality of architecture. Buildings that are energy-efficient, use sustainable materials, and minimize environmental impact are increasingly seen as examples of good architecture. Conversely, buildings that disregard environmental concerns can contribute to ecological problems and are often criticized for their short-sightedness.

Additionally, architects must consider the historical and cultural context of their work. Respecting and reflecting the local heritage and cultural values in design can enhance the relevance and acceptance of a building within its community. Ignoring these aspects can lead to a sense of alienation and disconnection from the local context. The decision of what experience to create in architecture is multifaceted, involving aesthetic, functional, social, environmental, and cultural considerations. Good architecture is that which enhances the quality of life for its users, respects its environmental and cultural context, and contributes positively to the broader community. Bad architecture, on the other hand, often results from neglecting these critical aspects, leading to spaces that fail to meet the needs and expectations of their inhabitants and society at large.

Defining Architecture in the Human Context

Ultimately, architecture is a multifaceted discipline that encompasses various forms and functions. It is a human experience at its heart, shaped by the architects’ choices in design, meaning, and emotional impact. The responsibility lies with the architects to decide whether their work will positively contribute to the world, enhancing the well-being of those who experience it. The distinction between good and bad architecture, therefore, is deeply rooted in these personal and collective experiences.